FunnyMoney++

“I’m sorry, but you’re out of convenience points”.

crap.

At that moment there really isn’t anything worse the sweet lady at the on-campus Starbucks could have told me - especially with a major exam just a few hours away.

“Can I pay with cash?”

“No, we only accept convenience points at this location.”

“Double crap. Looks like I’ll have to add some more points to my account.”

While I could for sure dig up a couple funny stories from my daily encounters with the Starbucks lady at BU’s student union, I’m not sure any are blog post worthy. As much as I know you’d like to hear more about our relationship and what happens next…

Does she make Alex’s day and give him a free coffee?

Does Alex grab the coffee and make a dash for the door with half the student union in hot pursuit?

Does Alex pass his test?

…this post will not have much to do with the Starbucks lady (for lack of her true name), but rather focus on a major security flaw I discovered in Boston University’s convenience point system.

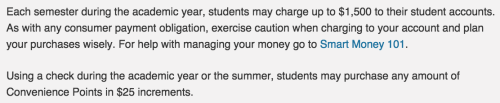

While BU makes it pretty damn difficult to get your caffeine fix, they couldn’t make it easier to charge your parents’ credit cards. All you need to do is log into your account and select how much money you’d like to add. $25.00, $50.00, $75.00, $100.00 … wait a minute. My espresso costs no more than $3.00 and you’re telling me the smallest amount I can add is $25.00? This can’t be right. Maybe the More Information link in the footer of the page will explain this nonsense.

-

”..students may only charge up to $1,500 to their student accounts.” – I need to temporarily relieve my caffeine addiction, not buy a new rolex.

-

“…students may purchase any amount of Convenience Points in 25$ increments” – My espresso costs $1.50. This is Starbucks, not some hipster coffee shop in Jamaica Plain selling $20.00 cappuccinos.

There’s got to be a way around this.

Goal: Add as many or as little convenience points as we’d like.

It should be just as simple to add $1.00 as it is to add $987.94.

We’re developers, and as developers the internet is our playground, therefore its time to have a little fun. There’s surely a way around this small inconvenience, the real question isn’t how we’ll find a solution, but will we find a solution before my espresso gets cold?

Let’s take a look at the current page to add convenience points. A quick glance towards the right side of the page we notice a form - the most basic way to post data to a server. This looks like a good place to start digging. Diving in we’ll begin to take notes of its structure. From the looks of it, it follows the basic web form format:

example web form:

<form action="url_to_submit_to">

<select>

<option>$1.00</option>

<option>$2.00</option>

<option>$3.00</option>

</select>

<input type="submit">

</form>

All forms are denoted by a <form> element. The action attribute tells the

form where to send its data on submission - almost always to some script on

some server to be processed. Nested within this element you’ll find elements

that let the user complete the form. In our case we have a list of <option>

tags. These allow the user to select one option from drop-down list.

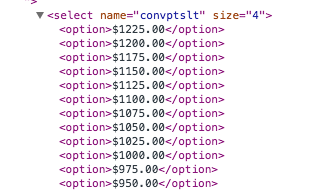

actual form source:

Scrolling through the option elements it turns out, as expected, each option is incremented by $25.00, making it impossible to submit any value that isn’t a multiple of 25 , right? Well, not so fast. We’re developers, and as developers the internet is our playground, so let’s have a little fun.

Client-Side Sanitization

To kick things off let’s talk about input sanitization. This is

the idea that you can never trust your users. Let’s say, hypothetically, we’re

a team of engineers building an application for students at a major University

to add real money to their student account. Sound familiar? Of course we want

our students to have the ability to add enough money to eat, buy coffee,

snacks, etc. At the same time we know it would be extremely dangerous to allow

young adults to charge as much money as they would like to their parents’

credit cards. After some long, boring meetings the team comes up with the

number 1500. No student will be able to charge more than $1500.00 to his/her

student account per semester. Great, our team can begin designing the proposed

web application. For simplicity let’s pretend our team decides on a very basic

database schema. It has one table, a Users table, containing a few columns.

Shown graphically:

=============================================

Users

| Name | Age | Graduation_Year | Major | Account_Balance |

==============================================

example user:

==============================================

| Alex | 22 | 2015 | Economics | 4.00 |

==============================================

For the sake of our discussion we only care about the Account_Balance column. This column should never exceed 1500.00 at any point - ever. There’s two ways to make sure this happens.

-

Client-Side sanitization

-

Server-Side sanitization

Web applications should implement both (fun fact: Boston University does neither)

If you’ve ever attempted to buy anything online you have most likely experienced both methods. After adding the items to your cart, the next step is usually to fill out credit card information. If you have ever forgotten to enter a required field, tried to go on to the next step, just to be stopped by an error message, then congratulations you’ve encountered client-side validation. It’s job is to make sure the data being submitted follows the format the server expects. Perhaps it expects a credit card number, and since you didn’t enter one it throws an error and will not let you submit the form until it has been filled in. Client-side sanitization solves this problem of making sure form-data is valid, right? Well, sort of. The problem with client-side validation is that there are plenty of ways to get around it. In order to sanitize input on the client, a program runs some JavaScript and checks some values against some other values. This works great, until you realize anyone can very simply disable JavaScript in their browser. Another larger problem, is that technically any user (with the right knowledge) can submit any value they’d like to a server - hell we don’t even need a form. Fuck it we don’t even need a web browser! (read: HTTP POST requests if you’re curious what I’m talking about). This knowledge will come in handy in a minute.

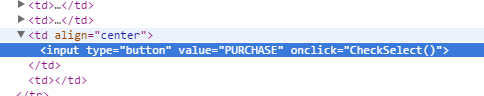

Anwyays, let’s get back to the problem at hand. All we want is the ability to add any amount of money we’d like to our student account. Let’s begin with $1.00. So far, we’ve found a form for submitting data to the server. It looks like a typical HTML form, and contains a number of option elements that allow users to submit dollar amounts - multiples of 25. We still have one element remaining that needs to be inspected - the submit button. Opening our developer console, we take one last dive into the source code. And behold, the next clue! Reading from left-to-right, the input element has its required attributes:

type="button" value="PURCHASE"

The money is in what lies next:

onclick="CheckSelect()"

A javascript event handler! Without going into detail, this is a way to tell

this element, “Hey button! When a user clicks on you, execute the function

CheckSelect()”

If only we could find out what CheckSelect() actually does. Well, lucky for

us, in order for the browser to execute any JavaScript, it must first be

downloaded from the server. Therefore, we have actually, whether we wanted to

or not, downloaded the file containing this function. We just need to find it.

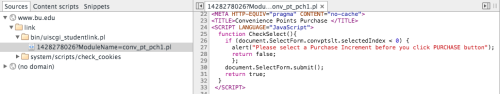

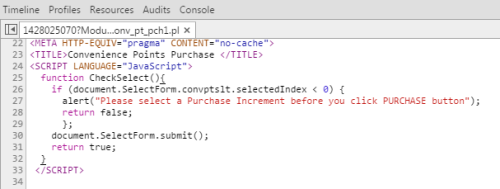

The first place to look is the Sources tab of Chrome’s Developer Tools. This

tab lets us see every script that’s a part of the current page. Looking

through the scripts, we soon notice 1428278026ModuleName=conv_pt_pch1.pl (From

the .pl file extension we can infer it is a Perl script - which might tell us

more about the developers than the actual software lol). What do you know, its

not minified or obfuscated! Doing a quick CMD-F search for CheckSelect()

takes us directly to the function definition:

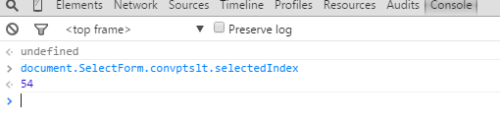

At first, we’d most likely think an event handler attached to a

form submit would handle some sort of client-size sanitization or AJAX request,

but upon closer inspection this is not the case for our button. Before digging

deeper and figuring out what document.SelectForm.convptslt.selectedIndex even

returns, we can take a look at this function and conclude that all it does is

make sure that the user has indeed selected a dollar amount before submitting

the form.

Any developer familiar with JavaScript would understand that

document.SelectForm simply sets the SelectForm object as an attribute on the

document object. Taking a look at the attributes defined on this SelectForm

object you’ll notice two that stick out:

-

selectedIndex

-

selectedOptions

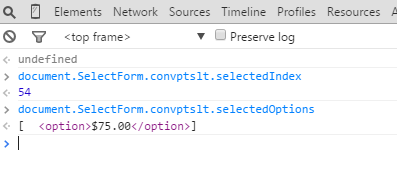

These attributes simply reflect which option the user has selected.

Looking back at the CheckSelect() function:

if(document.SelectForm.convptslt.selectedIndex < 0) {

alert( "please select a Purchase Increment before you click PURCHASE button");

return false

}

This confirms that all this function does is confirm the user has selected an option before submitting the form. Bad news for BU, but great news for us. Seeing that the developers used inline javascript to attach this event handler it is most likely the only function that will be triggered on submission, which brings us to an answer….No client-side sanitization! 1 down, 1 to go. Now we’ll need to check to see if these developers decided to take the extra five minutes and sanitize input server-side. There’s only one way to do this - send some data that should return an error and check to see if it persists to the database.

Server-Side Sanitization

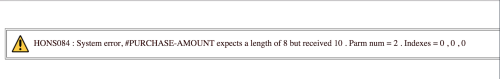

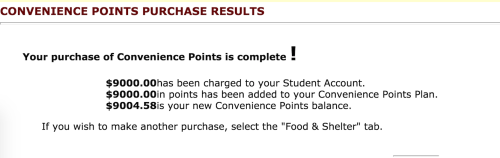

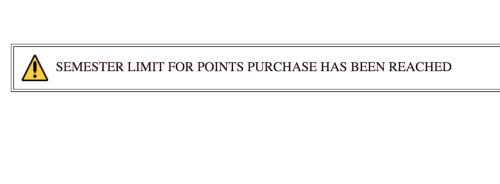

I don’t know about you, but I’m having a hell of a time. If we’re going to throw some data at this thing we might as well go big - like really fucking big. Given a BU student has added $0.00 to their account for this semester, the maximum they should be allowed to add is $1500.00. How about we double this amount?No, fuck that we said we’re going big. Let’s 67x this amount and chuck $100k at it - almost enough to pay for two semesters at BU with convenience points (haha). And this is exactly what we’ll do. Changing an input value to $100000.00, highlighting it to set SelectedOptions to it’s value, holding our breath, we’ll click PURCHASE..

HONS084: System error, #PURCHASE-AMOUNT expects a length of 8 but received 10. Parm num = 2 . Indexes=0 , 0, 0

Holy Shit.

Any developer handling server-side validation would have checked to make sure

the submitted value is not > ($1500 - total_amount_purchased_this_semester),

and redirected back to the form page displaying an error to the user. But this

is different. This is an un-handled, default error. And thus we’ve confirmed

it, no server-side sanitization.

Errors can tell you much more than you’d expect. While we don’t know for sure if our thinking is correct, it seems pretty damn plausible.

#PURCHASE-AMOUNT expects a length of 8 but received 10.

The error actually gave us the answer we’re looking for.

Checking the length of the form-data string sent to the server…

"$100000.00".length

=> 10

The error message says it expected a length of 10, but received 8. Therefore, let’s give it what it wants and send it a message with a length of 8.

“$9000.00”

Holding our breath once again…

fml.

“1000000” without dollar sign and period is also <= 8 characters. I’d love to try this amount, but at the moment its not really possible.

Stay Curious.

Check out FunnyMoney - a chrome extension I built to make this whole process much simpler. Just install the extension from the Chrome Web Store and now your student link will have options to purchase in increments of $1.00)

Follow up: I have informed BU Information Security of the issue and they are working on a fix.

The $9000.00 convenience points have been rebated, with this being said I don’t think anyone should add more than they’re permitted per semeter.