Procs, Blocks, Lambdas, and Lies

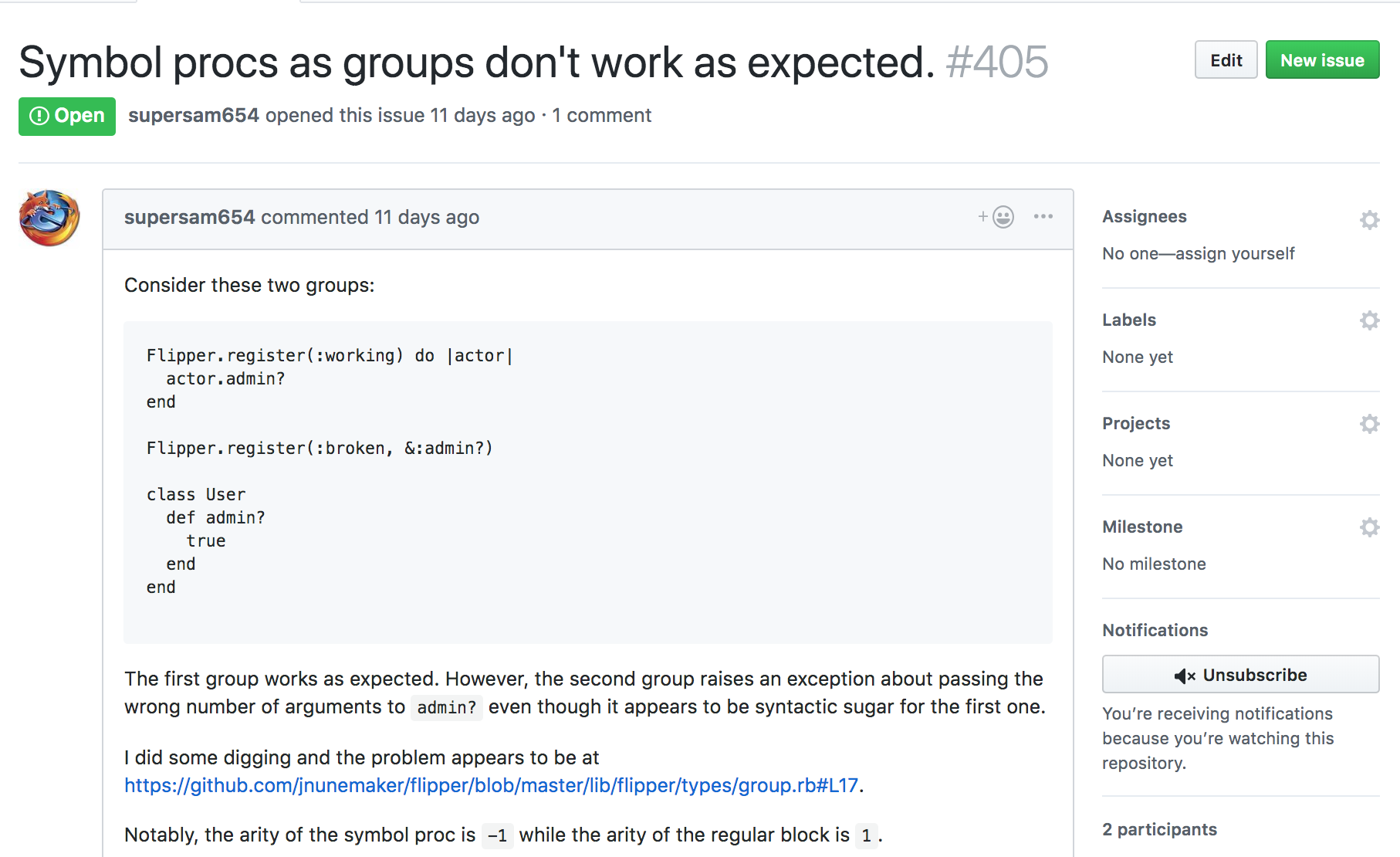

Github user supersam654 recently opened a great issue on the Flipper repo after running into trouble trying to

register a group using Ruby’s &:method shorthand.

Groups allow enabling features based on the return value of a block, which is passed the actor when checking for enabledness.

&:admin?

When Rubyists want to call a method on every member of an Enumerable we tend to avoid the extra keystrokes needed to type out the whole block:

["a", "b", "c"].map { |letter| letter.upcase }

#=> ["A", "B", "C"]

in favor of the more concise:

["a", "b", "c"].map(&:upcase)

#=> ["A", "B", "C"]

This works with any Enumerable method that yields each member of the collection to the provided block. If

this works with map, each, select, etc. why is supersam654 having trouble using it with

Flipper.register? To answer this we’re going to have to take a tour of some of the more advanced features

of Ruby. Let’s get started.

Registering Groups

When a Flipper group is registered it stores the provided block in an instance variable @block.

Given a simplified version of register:

def register(name, &block)

@block = block

end

When this code is executed:

Flipper.register(:working) do |actor|

actor.admin?

end

We end up with a gate instance that has a match? method locked and loaded, ready to check if a feature is enabled for an actor:

def register(name, &block)

@block = block # { |actor| actor.admin? }

end

def match?(thing, context)

if @block.arity == 1 # @block = { |actor| actor.admin? }

@block.call(thing)

else

@block.call(thing, context)

end

end

When checking if a feature is enabled for a given user, match? eventually gets called with the user and optionally the context if your provided block takes two arguments . The feature

is enabled for the user if the result of the block is true.

Arity

if @block.arity == 1 # @block = { |actor| actor.admin? }

@block.call(thing)

else

@block.call(thing, context)

end

Arity is the number of arguments a function takes (Thanks Wikipedia!, and screw you high school teacher who said Wikipedia was not a credible source for my essays!).

Ruby, with its powerful metaprogramming abilities lets us introspect any object we’d like including method objects. Who said Ruby methods aren’t first class citizens? To figure out a method’s arity we don’t need any special wizardry we just need to politely ask it.

def greet(person)

"Nice to meet ya #{person.name}"

end

method(:greet).arity

# => 1

def introduce(person1, person2)

"#{person1.name}, I'd like to introduce you to #{person2.name}"

end

method(:introduce).arity

# => 2

When a method takes a variable number of arguments arity returns -n-1, where n is the number of required arguments.

def call(*people)

people.each(&:call)

end

method(:call).arity

# => -1

Just like methods, procs and lambdas can also be asked their arity.

proc { |arg| }.arity

# => 1

->(arg) { }.arity

# => 1

lambda {|*args| }.arity

# => -1

Lies, Lies, and More Lies

I have to apologize for telling a slight lie earlier. The register method doesn’t just store the block in an

instance variable @block. When & is prepended to a parameter like &block Ruby converts the provided block

to a proc, which allows us to reference it by dropping the ampersand. You can name this whatever you want e.g. &foo. If passed an argument

prepended with & instead of a block, it converts the argument to a proc by calling to_proc on it.

def register(name, &block)

# Before giving us a refernce to block

# Ruby implicitly calls: block = block.to_proc

@block = block

end

When register is passed:

register(:admin, &:admin?)

The following happens:

def register(name, &:admin?)

# block = :admin.to_proc - Ruby calls this under the hood for us

@block = block

end

And what would happen if we checked this proc’s arity?

def register(name, &block)

# block = :admin.to_proc - Ruby calls this under the hood for us

@block = block

puts @block.arity

end

register(:admin, &:admin?)

# => -1

register(:admin) { |actor| actor.admin? }

# => 1

Hold up. With the block the correct arity is returned, but with &:admin? -1 is returned! This explains why

Flipper.register is working with blocks, but not the &:admin? shortcut.

def match?(thing, context)

if @block.arity == 1

@block.call(thing) # This path gets called with block

else

@block.call(thing, context) # This path gets called with &:admin and raises an exception

end

end

To figure out what exactly is happening here we’ll need to keep on digging.

I thought the following did the exact same thing…

["a", "b", "c"].map { |letter| letter.upcase }

["a", "b", "c"].map(&:upcase)

Almost, but not quite. This is because Symbol implements its own version of to_proc.

simplified version of Symbol#to_proc. The real implementation is now written in C

class Symbol

def to_proc

proc { |arg| arg.send(self) }

end

end

If we had a symbol such as :upcase,

when invoked:

["a", "b", "c"].map { |letter| letter.upcase }

["a", "b", "c"].map(&:upcase) # same as the shorthand

we could replace these variables to see what it would actually look like:

def to_proc

proc { |arg| arg.send(self)

# proc { |letter| letter.send(:upcase) }

end

Now we understand what this &:upcase business is all about, but that still doesn’t explain why the two

examples above aren’t actually the same. That’s beacuse I’ve lied done it again! Another lie! The real definition of

Symbol#to_proc looks more like this:

class Symbol

def to_proc

proc do |*args|

receiver, *rest = args

if rest.nil?

receiver.send(self)

else

receiver.send(self, *rest)

end

end

end

end

As seen in our simplified example above Symbol#to_proc always returns a proc that takes a variable number of

arguments, while blocks converted to procs via &block return procs that take the exact same number of

arguments as the block:

def arity(&block)

block.arity

end

arity() { |user| user.admin? }

# => 1

arity(&:to_s)

# => -1

This means that in the &:admin? case we end up in the else condition and pass arguments to

admin?, which expects 0. As always the computer does exactly what we tell it to do and not what we want it

to. The computer wins and an exception is raised.

def match?(thing, context)

if @block.arity == 1 # @block = { |actor| actor.admin? }

@block.call(thing)

else

@block.call(thing, context) # this path gets called

end

end

Ruby friends to the rescue

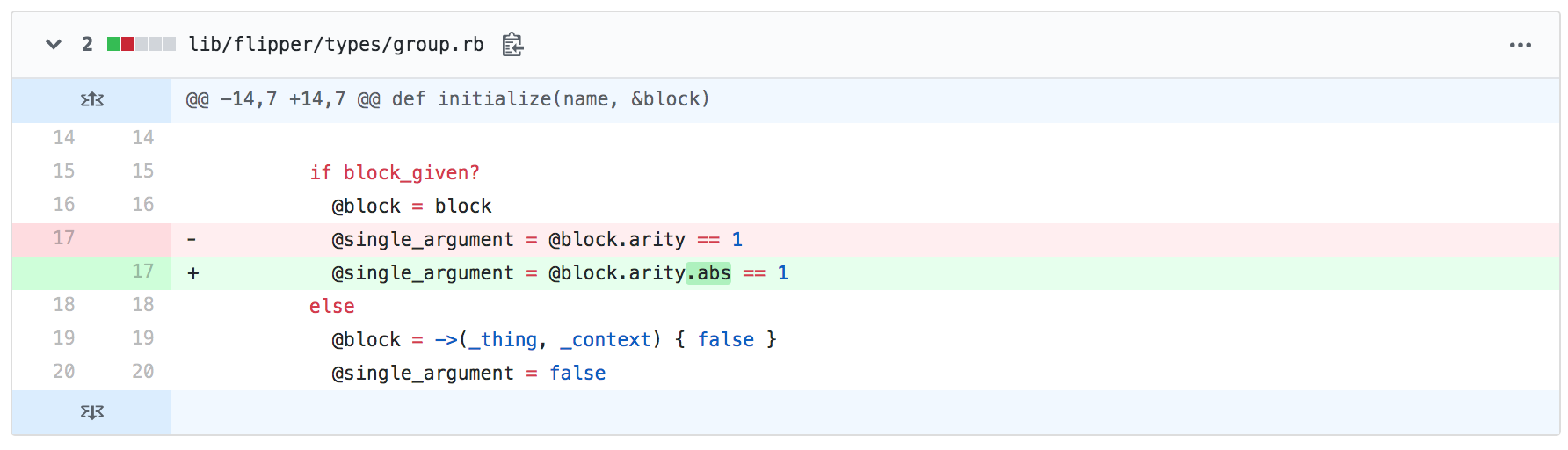

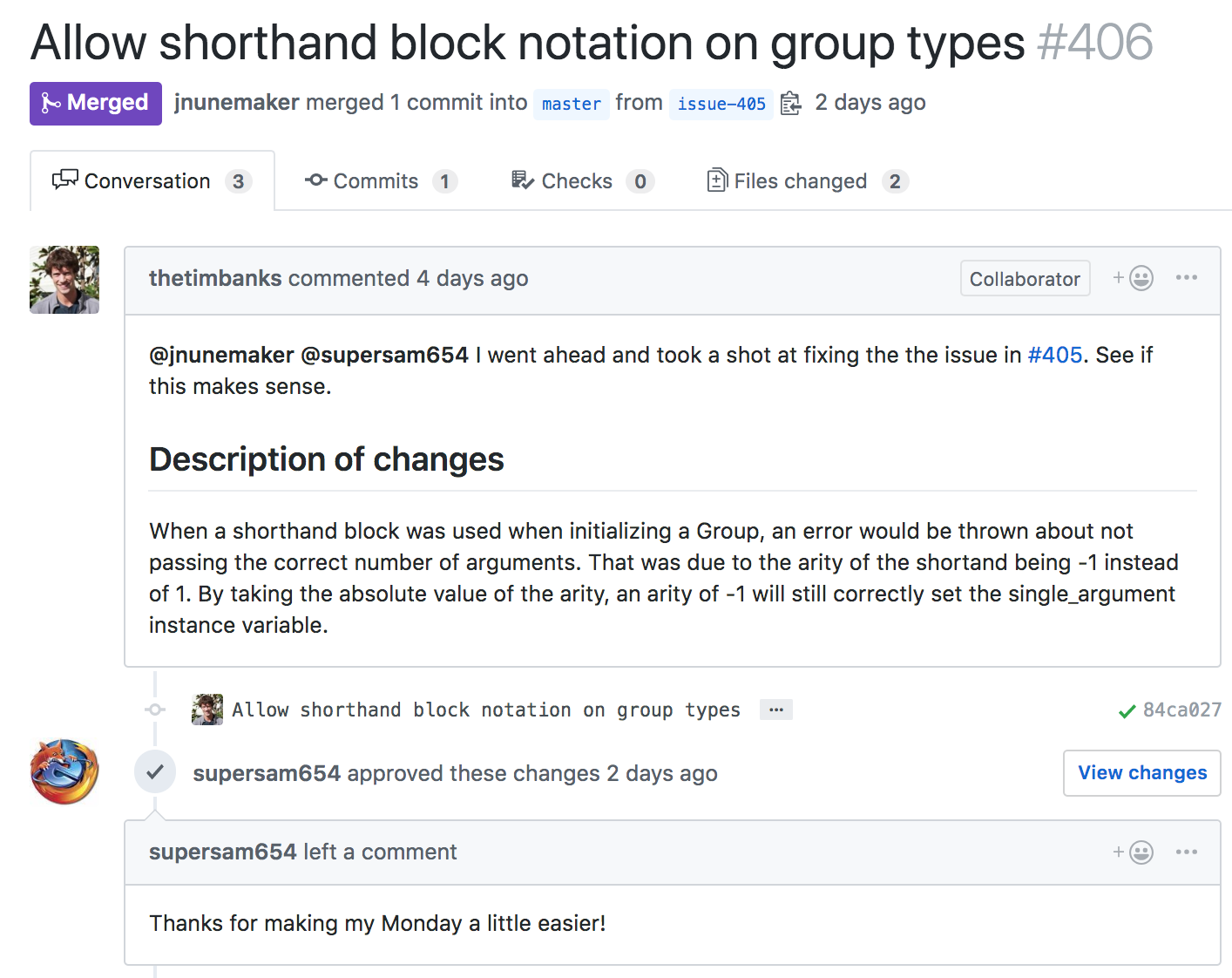

Tim, being the legend that he is opened a PR using Sam’s (also total legend - both of whom I’ve never actually met, but I’m sure they’re legends) proposed idea to take the absolute value of the arity in match.

Since this has been merged it should be going out in the next release after 0.16.2. As always check out the Changelog to be sure.

Follow Up

If you thought this was a fun dive into some parts of Ruby you may not have explored I encourage you to experiment and implement your own to_proc method. Think of some ways you can make it more powerful. I’ll get you started:

class String

def to_proc

proc { |arg| arg.send(self) }

end

end

["a", "b", "c"].map(&"upcase")